Sunday mornings, before mass, I try to experience God where I can. The attempt to experience God before mass, I realize, helps when I fail to have a spiritual experience at church, which is often. Should the music dry my already thirsty soul, should the homily fall in my expectations to be inspired to run out the church doors and give myself to the poor, should the cold handshake I receive from the person sitting in front of me bother me too much — I will have the morning as solace for church.

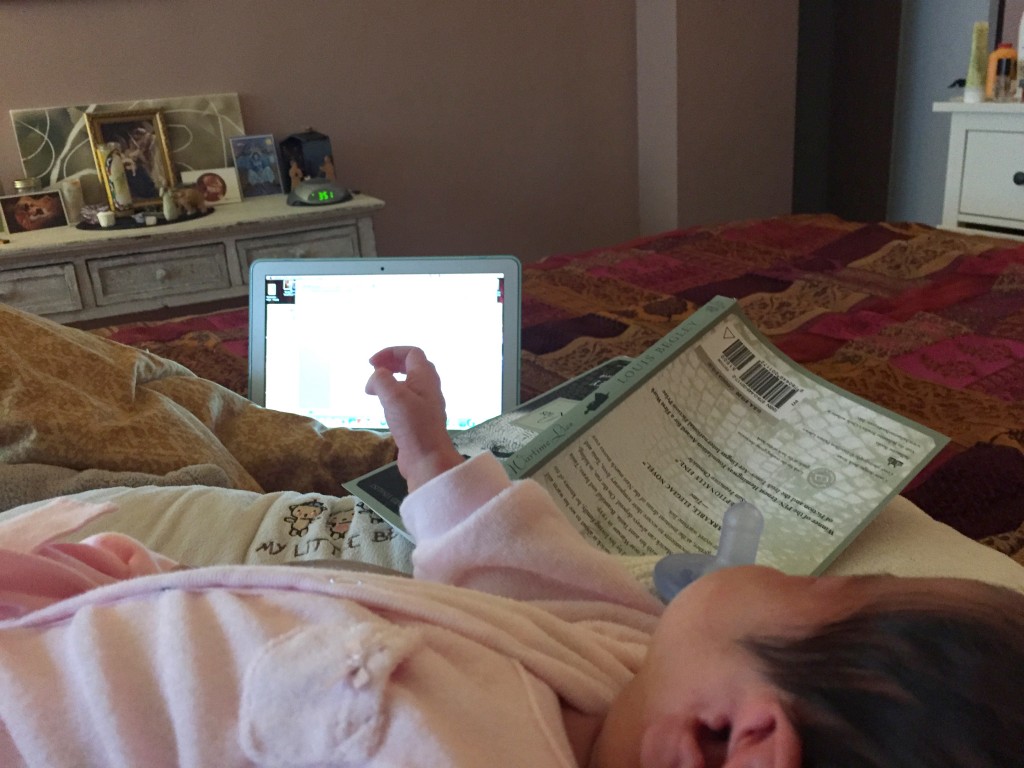

This morning I woke at 5am to a grunting baby. Rosario, greeting the world with small utterances from deep in her little body, drank and drank from my left breast. She quickly quieted herself, seemingly content that I anticipated her needs before her grunts grew into a full city-heard cry. My breakfast, egg whites and oatmeal, vanished without delay. My hunger after nursing Rosario demands fast preparation hands. Afterward, the stillness of the apartment and borrowed silence in the Bronx led me to the couch. Alone with nothing but a cup of coffee and a book. I knew it wouldn’t last so I dove into Dorothy Day’s, “The Long Loneliness,” her autobiography. Within the first pages, I became lost in her early explanations of how she was haunted by God, plagued by early realizations of good and evil, knowing good from bad. I resonated with her.

It brought early memories of my own family, especially my mother who, in raising four children, grew to depend on prayer and faith the way modern American housewives now depend on evening glasses of red wine. What struck me as especially inspiring is reading about (arguably) a modern day saint worker who confesses to the ordinary sins of life and Day’s ability to describe that mundane nature as inherent and natural as our right to breathe.

— Interruption: When I checked Facebook earlier, another writer asks how to write as a mother. And I write a few lines of encouragement, trying to bid her to the side of optimism. Remembering that life – writing, parenting, work – are all life practices that we hope to master but never truly succeed. As I write those lines and these, my son asks for help in stripping a tag off a new shirt, removing a plastic binding from a stamp he received as a gift, and Nick exits the shower with steam and carrying his iPhone, playing old rock songs. Each one perforates my silence, the caffeinated inspiration that has descended, temporarily, on me. And I try to write quickly, incisively, and with depth knowing, hating that the inspiration, like my morning breakfast will quickly evaporate into nothingness. This last line was interrupted once again by my son, asking for me to look at birthday card he made for his cousin. The clippings of conversation from the kitchen slide through from under the door. My breasts tingle, asking for either a baby’s latch or a pump. Interruptions, interruptions. —

Dorothy Day shares her earliest memories and the tone reminds me of an investigational hunt; the scouring for evidence, the search for bread crumbs that led her to the place where she writes the paragraphs about what made her Catholic. It moves me into deeper consciousness – my preferred place of existence – and a flood of memories surface. Irrelevant shards of childhood, splintered afternoons that I can only recall in patchy images – like my siblings and I trying to cook my parents dinner to celebrate their 20th anniversary, and my serving them plates of food on roller-skates – and with difficulty in understanding why my brain preserved that particular moment.

I remember afternoons staring into the blue sky, wondering about God, or what I thought God to be. New Jersey summer nights and the smell of the community pool, tv dinners, and 10 o’clock chides from my mother to the rest of the family to gather in the living room to pray the rosary. It occurs to me, in the stillness, when Rosario, Isaiah, and Nick are soothed by their dreams, that I can remember nearly everything important if I concentrate long enough and have enough stillness for my mind to recall what was long forgotten. If it had to do with God, I will remember it with enough coaxing.

The project I am about to endure is daunting. I don’t know where to begin a memoir about my faith, but what I do know is that I am no longer afraid to begin writing it. I am, however, still steeped in the fear of what I will unearth, but I have come to the conclusion that that fear is healthy, perhaps even necessary in my telling such a story. A story, I believe will probably be, the story of my life. (Double entendre: story of my life literally, story of my life referring to importance and ambition). Or maybe it just feels that way at the young age of 36 which IS young in the memoirist world. I remember when 30 was old. Such paradox, the writing age vs gestational age.

I keep thinking that this summer will deliver me from myself; like I will awaken as the person and writer I long to call myself, my skin clear of the self-inflicted bruises of perceived inferiority and doubt. Someone without a shadow following me. I continue doubting my ability to write despite a growing list of publications, even after a year of studying in a writing program. The irony catches me, confounds me. This explains whey I find such comfort in Day’s writings. She began as a savvy journalist with an array of glittered literary friends in New York. But then a shift happens. She leaves the world of literature, art, and journalism and she writes of the decisions that eventually led her to pursue justice and a life of faith. What I read is the ultimate surrender to the haunting of what she described as a child. Perhaps it is the haunting that most comforts me, the knowing that if others are haunted, it is not my imagination that a Ghost indeed exists, and that same Ghost, the one that accompanies me from birth to my unknown death, has cloaked the shoulders of others, asking for their life. Her work gestures skyward as if to say, “There would be no shadow following you were the sun not shining over your shoulder.”

Writing about my faith is like asking me to fight in a war where I am both sides. The battle field’s territory is my interiority. There will only be one victor and one casualty, and they will be one in the same. But if I am truthful, the war has been waging for years. 36 years to be exact. Writing about it is just a formal sharing.